Effects of Urban Environment on Families and Women Near Turn of Century

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the growth of American cities in the late nineteenth century

- Identify the key challenges that Americans faced due to urbanization, as well as some of the possible solutions to those challenges

Urbanization occurred apace in the second one-half of the nineteenth century in the Usa for a number of reasons. The new technologies of the time led to a massive bound in industrialization, requiring large numbers of workers. New electric lights and powerful mechanism allowed factories to run xx-iv hours a day, 7 days a week. Workers were forced into grueling twelve-hr shifts, requiring them to live close to the factories.

While the work was dangerous and hard, many Americans were willing to leave behind the failing prospects of preindustrial agriculture in the promise of better wages in industrial labor. Furthermore, problems ranging from dearth to religious persecution led a new wave of immigrants to arrive from primal, eastern, and southern Europe, many of whom settled and found work near the cities where they first arrived. Immigrants sought solace and comfort amidst others who shared the same language and community, and the nation's cities became an invaluable economic and cultural resource.

Although cities such as Philadelphia, Boston, and New York sprang up from the initial days of colonial settlement, the explosion in urban population growth did not occur until the mid-nineteenth century. At this time, the attractions of city life, and in particular, employment opportunities, grew exponentially due to rapid changes in industrialization. Before the mid-1800s, factories, such as the early textile mills, had to be located near rivers and seaports, both for the transport of goods and the necessary h2o power. Production became dependent upon seasonal water flow, with cold, icy winters all just stopping river transportation entirely. The development of the steam engine transformed this need, allowing businesses to locate their factories near urban centers. These factories encouraged more and more than people to move to urban areas where jobs were plentiful, but hourly wages were ofttimes low and the work was routine and grindingly monotonous.

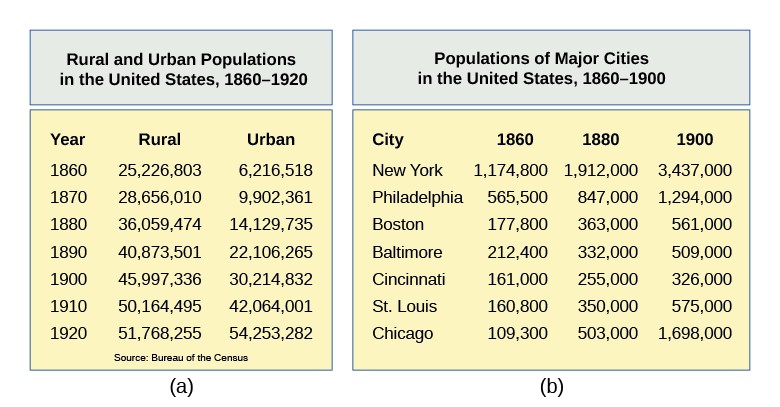

Equally these panels illustrate, the population of the U.s.a. grew rapidly in the late 1800s (a). Much of this new growth took place in urban areas (defined by the census as twenty-5 hundred people or more), and this urban population, especially that of major cities (b), dealt with challenges and opportunities that were unknown in previous generations.

Somewhen, cities adult their ain unique characters based on the core industry that spurred their growth. In Pittsburgh, it was steel; in Chicago, it was meat packing; in New York, the garment and financial industries dominated; and Detroit, by the mid-twentieth century, was defined by the automobiles it built. Merely all cities at this time, regardless of their industry, suffered from the universal issues that rapid expansion brought with it, including concerns over housing and living conditions, transportation, and communication. These issues were virtually e'er rooted in deep course inequalities, shaped by racial divisions, religious differences, and ethnic strife, and distorted by corrupt local politics.

This 1884 Bureau of Labor Statistics report from Boston looks in particular at the wages, living conditions, and moral code of the girls who worked in the clothing factories there.

THE KEYS TO SUCCESSFUL URBANIZATION

Equally the country grew, certain elements led some towns to morph into large urban centers, while others did not. The following four innovations proved critical in shaping urbanization at the turn of the century: electrical lighting, advice improvements, intracity transportation, and the rise of skyscrapers. Every bit people migrated for the new jobs, they often struggled with the absence of basic urban infrastructures, such every bit better transportation, acceptable housing, means of communication, and efficient sources of lite and energy. Fifty-fifty the bones necessities, such as fresh water and proper sanitation—often taken for granted in the countryside—presented a greater challenge in urban life.

Electric Lighting

Thomas Edison patented the incandescent light bulb in 1879. This evolution quickly became common in homes equally well as factories, transforming how fifty-fifty lower- and middle-class Americans lived. Although slow to arrive in rural areas of the country, electric power became readily available in cities when the first commercial power plants began to open in 1882. When Nikola Tesla subsequently developed the Ac (alternating current) system for the Westinghouse Electrical & Manufacturing Visitor, ability supplies for lights and other manufacturing plant equipment could extend for miles from the power source. Air-conditioning power transformed the use of electricity, allowing urban centers to physically cover greater areas. In the factories, electric lights permitted operations to run twenty-4 hours a day, vii days a week. This increase in production required additional workers, and this demand brought more people to cities.

Gradually, cities began to illuminate the streets with electric lamps to allow the urban center to remain debark throughout the night. No longer did the pace of life and economic action ho-hum substantially at dusk, the way it had in smaller towns. The cities, following the factories that drew people there, stayed open all the time.

Communications Improvements

The phone, patented in 1876, profoundly transformed communication both regionally and nationally. The telephone rapidly supplanted the telegraph as the preferred form of communication; by 1900, over 1.5 million telephones were in use effectually the nation, whether as individual lines in the homes of some middle- and upper-grade Americans, or jointly used "political party lines" in many rural areas. Past allowing instant communication over larger distances at whatsoever given fourth dimension, growing telephone networks made urban sprawl possible.

In the aforementioned fashion that electrical lights spurred greater factory production and economic growth, the telephone increased business through the more rapid pace of demand. Now, orders could come constantly via telephone, rather than via mail-gild. More than orders generated greater production, which in turn required still more workers. This demand for boosted labor played a key role in urban growth, as expanding companies sought workers to handle the increasing consumer demand for their products.

Intracity Transportation

As cities grew and sprawled outward, a major challenge was efficient travel within the metropolis—from home to factories or shops, and then back again. Nearly transportation infrastructure was used to connect cities to each other, typically past rail or canal. Prior to the 1880s, the almost mutual form of transportation within cities was the omnibus. This was a large, horse-drawn railroad vehicle, oftentimes placed on fe or steel tracks to provide a smoother ride. While omnibuses worked adequately in smaller, less congested cities, they were not equipped to handle the larger crowds that developed at the shut of the century. The horses had to stop and rest, and equus caballus manure became an ongoing problem.

In 1887, Frank Sprague invented the electric trolley, which worked forth the aforementioned concept equally the omnibus, with a big carriage on tracks, just was powered by electricity rather than horses. The electric trolley could run throughout the day and night, like the factories and the workers who fueled them. But it also modernized less important industrial centers, such as the southern city of Richmond, Virginia. As early on as 1873, San Francisco engineers adopted pulley technology from the mining industry to introduce cable cars and turn the urban center's steep hills into elegant middle-class communities. However, as crowds continued to grow in the largest cities, such as Chicago and New York, trolleys were unable to move efficiently through the crowds of pedestrians. To avert this claiming, city planners elevated the trolley lines in a higher place the streets, creating elevated trains, or L-trains, equally early as 1868 in New York City, and rapidly spreading to Boston in 1887 and Chicago in 1892. Finally, as skyscrapers began to dominate the air, transportation evolved one pace further to move hole-and-corner as subways. Boston'southward subway organization began operating in 1897, and was quickly followed by New York and other cities.

Although trolleys were far more efficient than horse-drawn carriages, populous cities such as New York experienced frequent accidents, equally depicted in this 1895 illustration from Leslie'southward Weekly (a). To avoid overcrowded streets, trolleys soon went cloak-and-dagger, as at the Public Gardens Portal in Boston (b), where iii different lines met to enter the Tremont Street Subway, the oldest subway tunnel in the United States, opening on September ane, 1897.

The Rise of Skyscrapers

While the applied science existed to engineer alpine buildings, information technology was non until the invention of the electric elevator in 1889 that skyscrapers began to take over the urban landscape. Shown here is the Dwelling house Insurance Building in Chicago, considered the first modern skyscraper.

The last limitation that large cities had to overcome was the always-increasing need for space. Eastern cities, unlike their midwestern counterparts, could not proceed to abound outward, as the land surrounding them was already settled. Geographic limitations such every bit rivers or the declension besides hampered sprawl. And in all cities, citizens needed to be close plenty to urban centers to conveniently admission piece of work, shops, and other core institutions of urban life. The increasing cost of existent estate made upward growth attractive, and so did the prestige that towering buildings carried for the businesses that occupied them. Workers completed the first skyscraper in Chicago, the 10-story Dwelling house Insurance Building, in 1885. Although engineers had the capability to go college, thank you to new steel construction techniques, they required some other vital invention in order to brand taller buildings viable: the elevator. In 1889, the Otis Elevator Visitor, led past inventor James Otis, installed the starting time electric lift. This began the skyscraper craze, allowing developers in eastern cities to build and market prestigious real estate in the hearts of crowded eastern metropoles.

Jacob Riis and the Window into "How the Other One-half Lives"

Jacob Riis was a Danish immigrant who moved to New York in the tardily nineteenth century and, subsequently experiencing poverty and joblessness beginning-manus, ultimately built a career as a police reporter. In the course of his work, he spent much of his time in the slums and tenements of New York'due south working poor. Appalled by what he found at that place, Riis began documenting these scenes of squalor and sharing them through lectures and ultimately through the publication of his book, How the Other Half Lives, in 1890.

In photographs such as Bandit's Roost (1888), taken on Mulberry Street in the infamous Five Points neighborhood of Manhattan's Lower E Side, Jacob Riis documented the plight of New York City slums in the belatedly nineteenth century.

By virtually contemporary accounts, Riis was an effective storyteller, using drama and racial stereotypes to tell his stories of the ethnic slums he encountered. Merely while his racial thinking was very much a product of his fourth dimension, he was also a reformer; he felt strongly that upper and eye-course Americans could and should care about the living conditions of the poor. In his book and lectures, he argued against the immoral landlords and useless laws that immune dangerous living atmospheric condition and loftier rents. He also suggested remodeling existing tenements or edifice new ones. He was not alone in his concern for the plight of the poor; other reporters and activists had already brought the issue into the public eye, and Riis's photographs added a new element to the story.

To tell his stories, Riis used a series of deeply compelling photographs. Riis and his group of amateur photographers moved through the diverse slums of New York, laboriously setting upwards their tripods and explosive chemicals to create enough light to take the photographs. His photos and writings shocked the public, made Riis a well-known figure both in his day and beyond, and eventually led to new state legislation curbing abuses in tenements.

THE Immediate CHALLENGES OF URBAN LIFE

Congestion, pollution, crime, and disease were prevalent problems in all urban centers; city planners and inhabitants akin sought new solutions to the bug caused by rapid urban growth. Living conditions for about working-class urban dwellers were atrocious. They lived in crowded tenement houses and cramped apartments with terrible ventilation and substandard plumbing and sanitation. As a event, disease ran rampant, with typhoid and cholera common. Memphis, Tennessee, experienced waves of cholera (1873) followed by yellow fever (1878 and 1879) that resulted in the loss of over ten chiliad lives. By the late 1880s, New York Urban center, Baltimore, Chicago, and New Orleans had all introduced sewage pumping systems to provide efficient waste management. Many cities were also serious fire hazards. An average working-class family of vi, with 2 adults and four children, had at best a ii-bedroom tenement. By one 1900 estimate, in the New York City borough of Manhattan lonely, there were nearly fifty thousand tenement houses. The photographs of these tenement houses are seen in Jacob Riis'due south book, How the Other Half Lives, discussed in the characteristic in a higher place. Citing a study past the New York Country Associates at this fourth dimension, Riis found New York to be the most densely populated city in the world, with equally many as 8 hundred residents per foursquare acre in the Lower East Side working-grade slums, comprising the Eleventh and Thirteenth Wards.

Visit New York Metropolis, Tenement Life to go an impression of the everyday life of tenement dwellers on Manhattan'southward Lower Eastward Side.

Churches and civic organizations provided some relief to the challenges of working-class metropolis life. Churches were moved to intervene through their conventionalities in the concept of the social gospel. This philosophy stated that all Christians, whether they were church leaders or social reformers, should exist as concerned near the weather of life in the secular earth as the afterlife, and the Reverend Washington Gladden was a major abet. Rather than preaching sermons on sky and hell, Gladden talked most social changes of the fourth dimension, urging other preachers to follow his lead. He advocated for improvements in daily life and encouraged Americans of all classes to piece of work together for the betterment of lodge. His sermons included the message to "dearest thy neighbor" and held that all Americans had to work together to aid the masses. As a result of his influence, churches began to include gymnasiums and libraries too every bit offering evening classes on hygiene and health care. Other religious organizations similar the Salvation Ground forces and the Immature Men's Christian Association (YMCA) expanded their reach in American cities at this time as well. Starting time in the 1870s, these organizations began providing community services and other benefits to the urban poor.

In the secular sphere, the settlement house movement of the 1890s provided additional relief. Pioneering women such every bit Jane Addams in Chicago and Lillian Wald in New York led this early progressive reform movement in the Usa, building upon ideas originally fashioned by social reformers in England. With no particular religious bent, they worked to create settlement houses in urban centers where they could help the working class, and in particular, working-class women, discover aid. Their help included child daycare, evening classes, libraries, gym facilities, and free health intendance. Addams opened her at present-famous Hull House in Chicago in 1889, and Wald's Henry Street Settlement opened in New York six years later on. The motion spread speedily to other cities, where they non simply provided relief to working-class women simply also offered employment opportunities for women graduating higher in the growing field of social piece of work. Oftentimes, living in the settlement houses among the women they helped, these higher graduates experienced the equivalent of living social classrooms in which to practice their skills, which also frequently caused friction with immigrant women who had their own ideas of reform and self-improvement.

Jane Addams opened Hull House in Chicago in 1889, offering services and support to the city's working poor.

The success of the settlement house movement subsequently became the basis of a political agenda that included pressure for housing laws, kid labor laws, and worker'due south compensation laws, amid others. Florence Kelley, who originally worked with Addams in Chicago, afterwards joined Wald'due south efforts in New York; together, they created the National Child Labor Commission and advocated for the subsequent cosmos of the Children's Bureau in the U.S. Department of Labor in 1912. Julia Lathrop—herself a former resident of Hull House—became the offset adult female to head a federal government bureau, when President William Howard Taft appointed her to run the bureau. Settlement house workers too became influential leaders in the women's suffrage movement as well as the antiwar movement during World War I.

Jane Addams Reflects on the Settlement Firm Movement

Jane Addams was a social activist whose work took many forms. She is perhaps best known every bit the founder of Hull House in Chicago, which afterward became a model for settlement houses throughout the country. Here, she reflects on the office that the settlement played.

Life in the Settlement discovers above all what has been called 'the boggling pliability of human nature,' and it seems impossible to set any premises to the moral capabilities which might unfold under ideal civic and educational weather condition. Simply in guild to obtain these weather, the Settlement recognizes the demand of cooperation, both with the radical and the bourgeois, and from the very nature of the case the Settlement cannot limit its friends to any one political party or economic school.

The Settlement casts side none of those things which cultivated men have come to consider reasonable and goodly, only it insists that those belong as well to that peachy trunk of people who, because of toilsome and underpaid labor, are unable to procure them for themselves. Added to this is a profound conviction that the common stock of intellectual enjoyment should not exist difficult of access considering of the economic position of him who would approach it, that those 'best results of civilisation' upon which depend the effectively and freer aspects of living must be incorporated into our common life and take free mobility through all elements of society if we would have our commonwealth endure.

The educational activities of a Settlement, equally well its philanthropic, civic, and social undertakings, are but differing manifestations of the attempt to socialize republic, as is the very existence of the Settlement itself.

In addition to her pioneering piece of work in the settlement firm movement, Addams also was active in the women's suffrage movement too equally an outspoken proponent for international peace efforts. She was instrumental in the relief endeavor later on World War I, a delivery that led to her winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931.

Section Summary

Urbanization spread rapidly in the mid-nineteenth century due to a confluence of factors. New technologies, such as electricity and steam engines, transformed factory work, allowing factories to movement closer to urban centers and abroad from the rivers that had previously been vital sources of both water ability and transportation. The growth of factories—as well every bit innovations such as electrical lighting, which allowed them to run at all hours of the day and dark—created a massive need for workers, who poured in from both rural areas of the United States and from eastern and southern Europe. Every bit cities grew, they were unable to cope with this rapid influx of workers, and the living conditions for the working form were terrible. Tight living quarters, with inadequate plumbing and sanitation, led to widespread illness. Churches, borough organizations, and the secular settlement house move all sought to provide some relief to the urban working class, simply atmospheric condition remained brutal for many new metropolis dwellers.

Review Question

- What technological and economical factors combined to lead to the explosive growth of American cities at this time?

Answer to Review Question

- At the end of the nineteenth century, a confluence of events made urban life more desirable and more than possible. Technologies such as electricity and the telephone immune factories to build and grow in cities, and skyscrapers enabled the relatively modest geographic areas to continue expanding. The new need for workers spurred a massive influx of task-seekers from both rural areas of the United States and from eastern and southern Europe. Urban housing—as well equally services such as transportation and sanitation—expanded accordingly, though cities struggled to cope with the surging demand. Together, technological innovations and an exploding population led American cities to grow as never earlier.

Glossary

settlement house movementan early on progressive reform motility, largely spearheaded by women, which sought to offer services such as childcare and free healthcare to assistance the working poor

social gospelthe belief that the church should exist every bit concerned about the weather of people in the secular world every bit it was with their afterlife

Source: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-ushistory2os2xmaster/chapter/urbanization-and-its-challenges/

0 Response to "Effects of Urban Environment on Families and Women Near Turn of Century"

Post a Comment